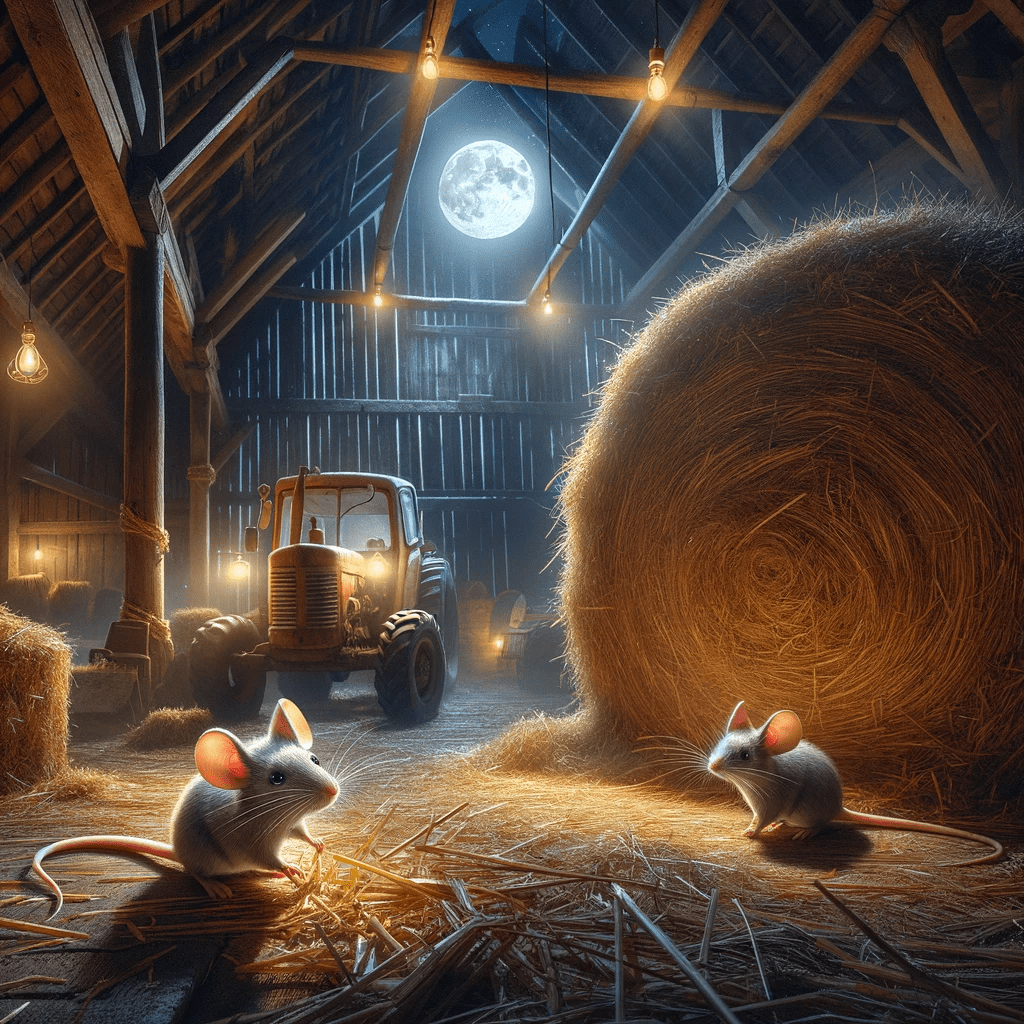

In the whispering darkness of Farmer McGregor’s barn, lived a colony of curious blind mice. Their world was one of rustling hay, fragrant wheat, and the ever-present hum of the grain thresher. But for the mice, the barn held a more profound mystery – the legend of the Big Father Mouse.

Pip, a mouse of sharp senses, navigated the barn with a tactile finesse. For him, the well-worn grooves in the wooden beams and the scent of oats strewn near the grain bin were not just familiar; they were his map, his guiding light. Each rustle and creak in the barn was a familiar tune, leading him to rich pickings and overlooked treats. Pip’s knowledge of the barn was built not on folklore but on the tangible echoes of his many adventures.

Millie, on the other hand, held a more mystical view. She revered the Big Father Mouse, an unseen guardian whose generosity, she believed, kept their barn-home prosperous. Guided by whispers of faith rather than sensory cues, Millie would eagerly investigate every unexpected noise, convinced it was the Big Father bestowing a hidden gift.

One chilly night near a massive haystack, their paths intersected. Pip, with his nose quivering, was certain it held nothing but stale remnants. He turned to leave, but Millie, with her ears alert, urged they explore the haystack.

“The Big Father Mouse has left us a feast!” she squeaked, eyes wide.

Pip skeptical, retorted. “There’s nothing there but shadows, Millie. Trust your whiskers, not whispers.”

Unswayed, Millie shook her head. “The Big Father Mouse always knows our needs. Come, Pip, just this once.”

With a sigh, Pip followed Millie. As they neared the haystack, a low rumble shook the floor. Fear prickled Pip’s fur. Millie, however, squealed with delight.

“He’s coming!” she chirped, ears twitching.

Suddenly, the rumbling intensified. A colossal, mechanical behemoth thundered towards them. Paralyzed with fear, Millie’s whiskers quivered. Instinctively, Pip seized her paw and darted away, relying on his memorized paths, his heart racing

They eventually reached the safety of a forgotten burrow beneath the floorboards. Panting, Millie huddled close to Pip, her eyes shining with gratitude.

“I don’t think that wasn’t the Big Father Mouse,” she whimpered, remorse filling the cracks in her voice.

Pip nuzzled her gently. “I don’t think so either, Millie,” he said softly. “Perhaps, sometimes, our senses and memories are all the Big Father Mouse we need.”

From that day on, Millie still believed in the Big Father Mouse, but Pip’s wisdom stayed with her. She learned to trust her whiskers as much as her faith, navigating the barn with a blend of instinct and awareness. And so, the blind mice of Farmer McGregor’s barn lived on, guided by whispers and echoes, by faith and whiskers, forever finding their way in the darkness, each in their own way, knowing the barn, not through singular truth, but through the rich tapestry of belief and knowledge, woven together, nibble by nibble, squeak by squeak.

Belief vs. Knowledge: Navigating the Interplay in Ontological and Epistemological Inquiry

At the heart of philosophical inquiry lies a fundamental tension: the distinction between belief and knowledge. This tension becomes particularly poignant when comparing ontological and epistemological approaches. Ontology asks “what exists?” while epistemology asks “how do we know?”. Within this seemingly straightforward distinction lies a complex interplay between what we hold as true and what we can demonstrably justify. Navigating this interplay is crucial for both understanding the nature of reality and the limitations of our own understanding.

Ontological investigations often start with pre-existing beliefs about the world. These beliefs, shaped by personal experiences, cultural frameworks, and historical trajectories, inform the kinds of entities and relationships we deem worthy of exploration. For example, a realist’s ontological inquiry may privilege objective entities like physical objects and abstract concepts, while a constructivist might focus on socially constructed realities and subjectively held meanings. While these starting points are distinct, the challenge lies in recognizing their influence on the very structure of inquiry. Can we truly identify objective features of reality if our search is guided by pre-existing beliefs about what such features might be? This is where epistemology steps in.

Epistemology sheds light on the mechanisms of knowledge acquisition and justification. By critically examining the methods and evidence used to support ontological claims, it helps us distinguish between mere belief and well-founded knowledge. For instance, rigorous empirical observation and experimentation, hallmarks of scientific epistemology, can bolster ontological claims about the material world. Similarly, qualitative research focused on lived experiences can illuminate social realities that might be missed by purely objective methods. Yet, even within these seemingly robust frameworks, epistemology cautions against the pitfalls of dogmatism. Biases can creep into research design, evidence can be interpreted through pre-existing lenses, and limitations of our methodologies can inadvertently skew our understanding of reality.

The interplay between belief and knowledge becomes even more intricate when considering alternative ontologies. For instance, the belief in spiritual or immaterial realities presents ontological challenges that our usual empirical tools might not readily address. Epistemology, in such cases, can encourage us to broaden our methodological toolbox, seeking alternative ways of knowing that extend beyond the boundaries of traditional scientific inquiry. By acknowledging the role of personal experience, intuition, and cultural worldviews, we can open ourselves to previously marginalized ontologies, even if they cannot be definitively “proven” in the same way as material realities.

Ultimately, the tension between belief and knowledge, rather than being a stumbling block, serves as a driving force for both ontological and epistemological inquiry. By questioning our pre-existing beliefs, subjecting them to rigorous justification, and acknowledging the limitations of our knowledge, we can refine our understanding of reality and expand the scope of what we can consider to be “knowable.” Engaging in this critical dialogue between belief and knowledge allows us to not only map the terrain of existence but also navigate the intricate pathways of our own understanding. It is in this dance between belief and knowledge that we discover the true richness and complexity of the philosophical endeavor.